On his very first day in office, America’s new president, Donald Trump, enacted strict anti-immigration measures. However, in this regard, Russia has been ahead of Trump. The lives of migrants in Russia are complicated not only by laws but also by difficult relations with the local population, which knows little about newcomers, does not understand them, and has no desire to try. Migrants, in turn, respond to Russians with distrust and show little willingness to truly integrate into society.

The Mysterious Russian Soul

Erkin, the janitor responsible for maintaining the courtyard, urged residents in the building’s group chat: «Don’t throw bottles and trash from the balcony; it’s uncultured."

Indeed, it was not only uncultured but also dangerous. A glass beer bottle falling even from a modest height could easily injure not only Erkin himself but any unsuspecting passerby. And a plastic bottle filled with water, flung from about the twelfth floor with a skilled hand, could ruin anyone’s day.

Yet Erkin’s pleas fell on deaf ears. Trash continued to rain down, and flying bottles disrupted the flight paths of crows and pigeons alike. Realizing that the fight for cleanliness was hopeless, Erkin left his janitorial job, switched to food delivery, and eventually moved out of the building altogether.

Erkin was a good guy—polite, cheerful, and well-liked by everyone. However, the bottle-throwers refused to change their habits. Though they were only a handful, even a spoonful of tar can spoil a barrel of honey.

When Erkin was a janitor, he would rescue kittens abandoned by their owners and try to find them good homes with kind people who didn’t yet have a pet. He struggled to understand why anyone would discard kittens. The Prophet Muhammad loved cats, and in Russia, they are even called «our lesser brothers»—a phrase Erkin learned from a writer who lived on the seventh floor. But how could one treat brothers this way, Erkin wondered. Would anyone throw family onto the street?

«The mysterious Russian soul,» Erkin thought as he swept the trash. «The enigmatic West..."

One evening, Erkin noticed something unusual near the building’s first entrance: delivery mopeds began arriving frequently after 7 p.m. Young men would dismount, disappear into the building for a while, and then leave one by one. Some even came on foot, likely trying to avoid drawing attention.

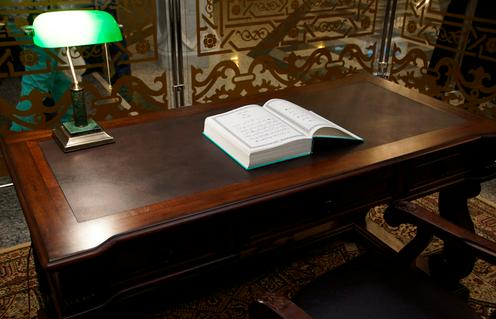

Erkin had a hunch about where they were headed—to the apartment on the eleventh floor where two brothers from Tajikistan lived. Perhaps they gathered to read the Quran with a mullah or a scholar, Erkin thought. The Quran is a complex book, written in Arabic, and it requires someone knowledgeable to explain its meanings to everyday Muslims.

«Maybe I should join them to listen to the Quran?» Erkin asked his wife.

«Don’t be ridiculous,» she replied. «For all you know, they could be terrorists. Stay home and watch TV."

Erkin wasn’t deeply religious, though he occasionally encountered people who were. Once, he took a taxi driven by a fellow Muslim. The driver wore earbuds and quietly repeated Quranic verses under his breath. A Russian passenger might have been alarmed, thinking the driver was reciting the shahada before a suicide bombing. But Erkin understood he was simply reading the Quran—after all, the more you read it, the closer you are to the Almighty. There are even angels called taliyat who continuously recite the Quran aloud, ensuring Allah’s word is always present in the world.

Eventually, the driver removed his earbuds, turned to Erkin, and asked: «Jihad is starting soon. Are you ready?"

Erkin was decidedly not ready for jihad and quickly exited the taxi, deciding to take the bus instead.

At the bus stop, a policeman and a man in military uniform approached him. They asked for his documents. Erkin handed over his passport.

«So you’re a Russian citizen?» the soldier asked, visibly pleased. «Are you registered for military service? Come on, let’s sign a contract…"

Looks with Contempt

The year 2024 was exceptionally tough for Russia. The terrorist attack at Crocus City Hall and Islamist uprisings in prisons were among the events that heavily impacted migrant workers, whose main «fault» was simply not being native Russians.

It should be noted that life for migrants had never been easy, but last year’s restrictive laws made it much more difficult. These laws regulate work, language proficiency, residency, and even family life for foreigners. There was even a proposal in the State Duma to ban migrants from bringing family members to Russia.

However, this is only one side of the coin. The other, equally significant side is the relationship between migrants and the local population. Here, mutual misunderstanding prevails, breeding fear and distrust.

Integration of migrants is a challenging issue everywhere, not just in Russia. Take Western Europe, for example. Fifteen years ago, German Chancellor Angela Merkel declared that the attempt to build a multicultural society had failed.

In Russia, however, the situation is somewhat simpler. In Europe, Muslim migrants often arrive with little understanding of local laws, customs, or language. In contrast, the countries of Central Asia have historical ties to Russia, having been part of both the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. This means that Uzbeks, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Tajiks are not as alien to Russians as Syrians, Turks, or Sub-Saharan Africans might be to Germans or Italians. The older generation of labor migrants speaks Russian reasonably well, and older Russians generally have a more positive attitude toward migrants, often seeing them as people rather than just a workforce.

Evidence of this can be seen in the fact that even after the terrorist attack at Crocus City Hall, the older generation’s attitude toward foreigners largely remained unchanged. However, according to migrants themselves, the younger generation tends to look at them with contempt.

Russia, being a multiethnic country, experiences slightly less tension in this regard. People here are somewhat accustomed to diversity. A Kazakh or Kyrgyz person might easily be mistaken for a Buryat due to their facial features, while a bearded Tajik could pass for a Caucasian. That said, even Russia’s own national minorities do not always receive ideal treatment.

The issue of the Other is often resolved according to circumstances—through personal interaction. A brief exchange of words, a shared smile, and suddenly, you’re not complete strangers anymore. Coexisting without mutual grievances or hostility becomes possible.

In reality, an average Russian doesn’t need to establish harmony with all the migrants in the country—it's enough to maintain a normal relationship with those they regularly interact with or occasionally encounter.

This is, of course, an ideal scenario. Slogans like “Russia for Russians” are no longer widely heard, but many still view migrants as second-class citizens, who might even pose a threat. Stories of migrant misconduct often come to mind, even though official statistics show that foreigners are responsible for only 4% of crimes committed in Russia.

Solving the problem of intolerance globally, once and for all, is almost impossible. Xenophobia is rooted in biology and instincts: if someone looks different, they’re perceived as an outsider—perhaps even an enemy. The situation becomes even more complex when the outsider not only looks different but also behaves differently.

Not long ago, religious migrants could be seen bowing deeply and praying on the streets of Russian cities, sometimes kneeling directly in the snow. For a devout Muslim accustomed to performing namaz five times a day, this behavior is perfectly normal. However, to the average Russian, it was unsettling. Who knows what these migrants might do next? Will they shout the Shahada and try to blow something up? It’s hard to predict what to expect from these bearded strangers—even if they don’t have beards.

Later, the trend shifted, and the behavior of migrants began to align more closely with the average Russian norm. Yet, this did little to address the issue of mistrust. Even those who admit to disliking migrants acknowledge there are admirable traits in their habits: they don’t get drunk, they respect elders, and they’re inclined toward compromise. But despite this, they remain outsiders, and no one knows what they’re planning, even when they smile—they are, after all, migrants.

Everybody Needs Them, but Nobody Likes Them

For most Russian citizens, migrants tend to blur into one indistinguishable group—few can tell a Tajik from a Kazakh. Perhaps that’s not even necessary. Ideally, people would look at the individual, not their nationality. Unfortunately, such an approach is beyond many.

In the current challenging circumstances, migrants are left with two behavioral strategies: smiles or stoicism. An old Chinese proverb says, “A smiling face doesn’t get hit by a fist.” But in reality, it does. A smile guarantees nothing here. Russians, from an early age, have heard the dismissive phrase: “What are you grinning at?”

Still, those who smile have a better chance of maintaining harmony with the people around them. As noted earlier, not all Russians harbor prejudices against migrants, and even fewer actively resent them. Many locals are polite, even welcoming. But if nine people smile at you and one spits in your face, that single act of contempt will linger more vividly than all the smiles combined. It stings deeply when kindness is met with hostility or aggression.

So, what’s the alternative—never smiling? Some migrants adopt a defensive stance of sternness, projecting an obvious unwillingness to engage with locals. Yet even such individuals often seek peace and mutual understanding. Sometimes you greet a migrant, and they won’t even acknowledge you. It doesn’t necessarily mean anything—they may still find a way to show they appreciated the gesture, perhaps by holding a door open for you later.

There’s no shortage of reasons for mutual resentment. Recently, migrants began complaining that attitudes toward them worsened due to rumors of high earnings in delivery services—up to 200,000 rubles a month. But whether wages are high or low, they seem to provide only a pretext for xenophobia. If migrants earn little, they’re looked down upon; if they earn a lot, they’re envied. Meanwhile, nothing stops a native Russian from taking the same delivery job. Some do, but most avoid it—the work is grueling and, let’s face it, not particularly promising. The kind of job that, conveniently, can always be left to migrants.

And here lies a paradox: everyone needs migrants, yet everyone seems dissatisfied with them. Strangely enough, the dissatisfaction is primarily directed at migrants from Central Asia, despite the fact that there are also migrants from Armenia, Belarus, and Moldova. Why is that? Could it be because Central Asia is a predominantly Muslim region?

Searching—and Not Finding

It’s clear that Islam is nothing new to Russians. Even official statistics estimate around 20 million Muslims living in Russia, primarily in regions like Tatarstan, Bashkortostan, and the Caucasus. But these are “our own,” familiar Muslims, the average person believes—so what should one expect from newcomers?

That said, even Russia’s own Muslims sometimes engage in baffling actions. Take, for instance, the infamous incident in Dagestan, where some people reportedly searched for Jews inside an airplane’s turbines. It wasn’t the searching itself that was offensive, but the fact that they didn’t find any.

Of course, such episodes, however absurd, are mere curiosities. What truly unsettles people isn’t the hunt for “airplane Jews” but the specter of Islamic radicalization. The average person, gripped by fear of jihad, often conflates Islam with terrorism, sometimes even equating the two—despite knowing next to nothing about the religion itself.

The politically correct narrative, of course, insists that Islam is a religion of peace. Yet in Russia, as in the rest of the world, terrorist attacks are occasionally carried out in the name of Allah. While such acts are universally condemned by world leaders, who often state that terrorists have no nationality, homeland, or religion, the unease persists. As deacon Andrei Kuraev once remarked with biting irony, we never hear news reports about a group of Taoists, Buddhists, or Jews hijacking planes or threatening to blow up shopping centers.

Naturally, it’s crucial to differentiate between radical Islam—sometimes referred to as Islamism—and individual, personal Islam. The latter serves as a spiritual guide for individual Muslims and their communities, or ummah. Radical Islam, on the other hand, focuses on political objectives, aiming to establish rigid theocratic states like Iran or even a global Islamic caliphate.

The pressing question that troubles many non-Muslims today is whether there is a clear and unbridgeable divide between traditional Islam and its radical counterpart—or whether the former could inevitably morph into the latter.

When it comes to Central Asia, the situation, while not perfect, is relatively stable. Most leaders of the current Central Asian republics—Turkmenistan being a notable exception—are shaped by Soviet-era secularism, where religion is kept separate from governance and its influence on society is limited. This has helped curb the growth of religious sects and terrorist organizations in the region, for now.

Still, much depends on the integrity of Islamic preachers—mullahs, imams, ulama, muftis, and sheikhs—who serve as mediators between the sacred texts and the faithful. This is particularly important because most ordinary Muslims in Central Asia do not speak Arabic. The Quran, written in Arabic, is considered the only authentic source of divine revelation, while translations into other languages are viewed merely as interpretations.

In any case, the Quran’s poetic and symbolic language requires careful interpretation. But above all, the Quran requires discernment—specifically, the discernment of good and evil.

To Each Their Faith

Here, it’s essential to touch on a topic that non-Muslims often overlook or remain unaware of: according to Islamic theology, Allah is the source of everything in existence, including both good and evil.

One of the core duties of a devout Muslim is to discern between good and evil—a task highlighted in the surah Al-Furqan. This responsibility is anything but simple, as even within the Quran itself, there are apparent ambiguities on this matter—at least, to an outsider.

One of the most debated interpretations concerns the Prophet Muhammad’s stance toward Jews and Christians. Advocates of radical Islam often cite surah Al-Ma’idah:

«O believers! Take neither Jews nor Christians as guardians—they are guardians of each other. Whoever does so will be counted as one of them. Surely Allah does not guide the wrongdoing people. You see those with sickness in their hearts racing for their guardianship.» (5:51-52)

However, a Russian Islamic philosopher Ali Polosin argues that the following verse clarifies this statement:

«O believers! Do not seek the guardianship of those given the Scripture before you and the disbelievers who have made your faith a mockery and amusement.» (5:57) In other words, this is not a blanket prohibition against all Jews and Christians but only against those who are antagonistic toward Islam.

Additionally, the Quran advises:

«Do not argue with the People of the Book (that is, with Jews and Christians — A.V.) unless gracefully, except with those of them who act wrongfully. And say, ‘We believe in what has been revealed to us and what was revealed to you. Our God and your God is ˹only˺ One. And to Him we ˹fully˺ submit.’”(surah Al-‘Ankabut, 29:46)

Finally, any and all disputes are resolved by the surah Al-Kafirun: «I will not worship what you worship, nor will you worship what I worship. You have your way, and I have my Way.» (109:1-6)

In reality, interfaith dynamics are far from simple. There are significant doctrinal differences between religions. For example, Muslims do not recognize Jesus as the Messiah or the Son of God, viewing him instead as a prophet. Additionally, followers of the Prophet Muhammad reject the Christian concept of the Trinity, seeing it as associating partners to Allah—a stance that raises questions about polytheism in Christianity.

It’s important to note that the Quran contains some knowledge about Christianity and Judaism, allowing devout Muslims to engage with these religions intellectually and even debate with non-believers. In contrast, largely due to historical factors, Westerners typically have only a rudimentary understanding of the Torah and the Gospel, with little to no exposure to Islamic teachings. In this regard, studying the Quran in Russia could be extraordinarily valuable—not only to better understand what we are dealing with in the present but also to prepare for what we might encounter in the future.

The Quran Does Not Prescribe Hatred

In the ideological and political realm, the initiative now lies with the followers of Islam. However, the main issue is not the doctrinal differences between religions, but how individual Muslims perceive those differences: Do they believe that these disagreements justify the killing of non-believers, or do they respect the right of others to follow their own path? This is where the core distinction between good and evil lies, as the Almighty allows the devout to exercise free will.

This is precisely what prevents a full-scale war of mutual destruction from breaking out. If all Muslims believed that Jews and Christians were enemies of the faithful, the world would have ceased to exist long ago. In this context, it is telling that not all Muslim countries supported the war waged by Hamas and Hezbollah against Israel. Some have remained neutral, while others, like Azerbaijan, have sided with the Jewish state.

Of course, even in the sacred book, one can find reasons for hatred and war if one looks for them. But if the goal is not to destroy the planet, we should focus not on what divides us, but on what unites us. And there is plenty of common ground to be found in nearly any religion.

One very important thing to remember is that the Quran does not prescribe hatred of non-believers.

In fact, doctrinally, the Quran is closely linked to both Judaism and Christianity. The Prophet Muhammad affirmed the truth of the revelations and laws given by the Almighty through the Old Testament prophets and Jesus Christ, clarifying only that people may have distorted these revelations and laws.

Islam is a young religion. It is passionate and naturally seeks expansion. It is dynamic, and just as tectonic processes occur in the Earth's crust, there are tectonic shifts within Islam as well. However, while magma is governed only by physical laws, religion also involves reason and free will. In this realm, it is not the particles of molten rock that are at play, but people—and people can choose how far they are willing to go in their relationships with others.

Islam is sometimes compared to Christianity during the time of the Crusades. But there is a difference. When the Crusaders, on their mission to reclaim the Holy Land, burned everything in their path, humanity was at a different stage. People's attitudes toward one another were very different then, which is why the Middle Ages are often called the Dark Ages. Today, we have the benefit of rich historical experience, and we are not obligated to repeat the mistakes—or the crimes—of the past.

Translated using the rendering of the Holy Quran in English by Dr. Mustafa Khattab.

-

14 February14.02From Revolution to Rupture?Why Kyrgyzstan Dismissed an Influential “Gray Cardinal” and What May Follow

14 February14.02From Revolution to Rupture?Why Kyrgyzstan Dismissed an Influential “Gray Cardinal” and What May Follow -

05 February05.02The “Guardian” of Old Tashkent Has Passed AwayRenowned local historian and popularizer of Uzbekistan’s history Boris Anatolyevich Golender dies

05 February05.02The “Guardian” of Old Tashkent Has Passed AwayRenowned local historian and popularizer of Uzbekistan’s history Boris Anatolyevich Golender dies -

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy

24 December24.12To Clean Up and to ZIYAWhat China Can Offer Central Asia in the “Green” Economy -

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

17 December17.12Gulshan Is the BestYoung Uzbek Karateka Becomes World Champion

17 December17.12Gulshan Is the BestYoung Uzbek Karateka Becomes World Champion