During August, Fergana plans to republish what we consider to be our most interesting ethnographic articles from previous years. Today we have decided to return to the last remaining island of the unique culture of the ancient Sogdians in Tajikistan. The article, written in 2015, tells the story of the Yaghnob Valley and its inhabitants.

In a remote mountain range in Tajikistan, at a height of 2,500-3,000 metres above sea level, live the last remaining speakers of the language of the ancient Sogdians. Over the next few decades, though, the unwritten Yaghnobi language may disappear completely – the number of people who speak it is declining sharply and whole swathes of the distinctive culture of the descendants of a several-thousand-year-old civilisation are being lost, while those who hold this heritage dear do their best to preserve it.

To this day, residents of the small number of villages in the Yaghnob Valley live in isolation from the outside world. Here there is no mobile phone reception or internet. Little has changed in the highlanders’ way of life for over a thousand years – they cultivate the land, grind their flour by hand, graze their livestock, raise their children and place their trust in the grace of God, all in complete harmony with the harsh but fantastically beautiful natural scenery around them.

For more than six months of the year, the valley’s 17 Yaghnobi villages, home to a total of around 500 people, are cut off from lower-lying settlements due to a lack of year-round road access. Between November and May, the single unpaved road leading up the Yaghnob River valley becomes impassable and dangerous due to rockfall and frequent avalanches and landslides.

Tragically, however, the Soviet policy of forced population transfers reached even to the Yaghnobis. In 1970, the authorities decided to move the whole population of the Yaghnob Valley to Tajikistan’s Zafarobod district in order to develop the cotton growing industry in this hot and arid region. Some families migrated close to the capital city Dushanbe, settling in the adjacent districts of Varzob, Vahdat and Rudaki. Before the forced transfer, there were 32 villages in Yaghnob with a population of more than 4,000 people. In one fell swoop, all of them were left deserted.

This was a deeply traumatic episode in the history of the Yaghnobis. The former mountain-dwellers settled into their new surroundings with immense difficulty. Due to the unaccustomed heat, the work in the cotton fields, the loss of their familiar foundations, and simply from the shock of the sudden collapse of their civilisation, in the first years of the transfer a large number of migrants died. In 1975, some Yaghnobis returned to their native land illegally, but in 1978 they were once again transferred to Zarafobod. A second wave of unauthorised returns started in the 1980s. Only with perestroika did the Yaghnobis gain the right to legally return to their homes. Some of them immediately headed back to their mountain villages. But some of them also resettled in other areas.

Today around 500 villagers live in Yaghnob itself (which belongs administratively to the Ayni District of the Sughd Region). Between two and fifteen families live in each of the 17 inhabited villages.

These days the largest number of Yaghnobis – up to 8,000 individuals – continue to reside in the Zafarobod district. Roughly another 7,000 have taken up residence in Dushanbe and in the Vahdat, Hisor, Varzob, Yovon and Rudaki districts. The most compact community of Yaghnobis is found in the Varzob district – in the village of Zuman, where over 100 families (around 800 people) live. Today’s Yaghnobis are thus dispersed all around the country, and those in Yaghnob itself are only a small part of the total population. As a result of this, researchers speak of a reduction in the number of speakers of the Yaghnobi language, and, consequently, of the danger of its extinction.

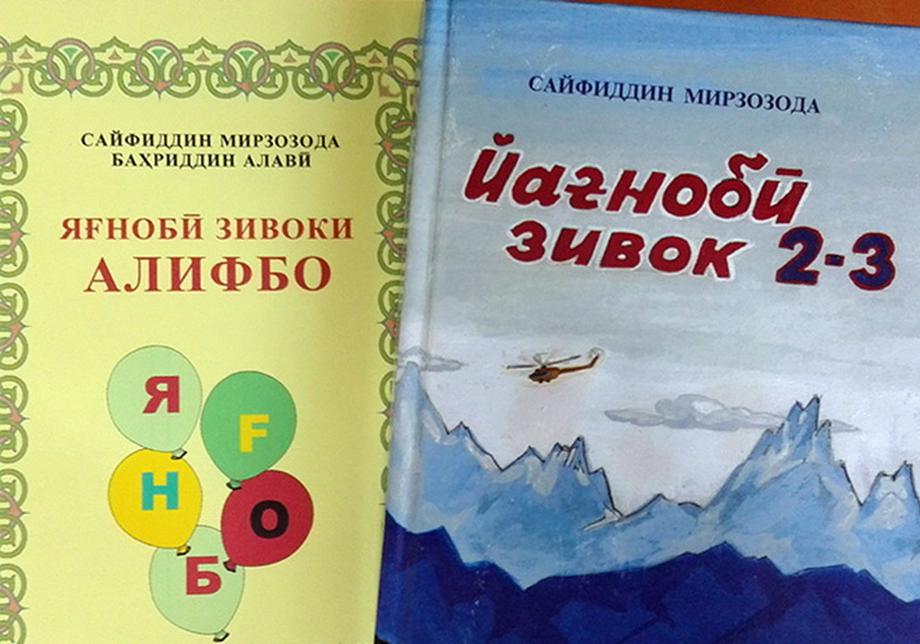

The Yaghnobis are the direct descendants of the Sogdians, the ancestors of contemporary Tajiks. But unlike the populations of other regions of Tajikistan, thanks to their isolation, Yaghnob Valley residents retained the ancient Sogdian language of their forefathers, part of the Northeastern Iranian language group. Until recently, the Yaghnobi language (sometimes called New Sogdian), which is spoken today by only a few thousand people, did not have a written form and is still classified by linguists as an unwritten language. It was only in the 1980s that a special Yaghnobi alphabet was devised on the basis of Cyrillic and the first school textbooks for young children were published in the local language.

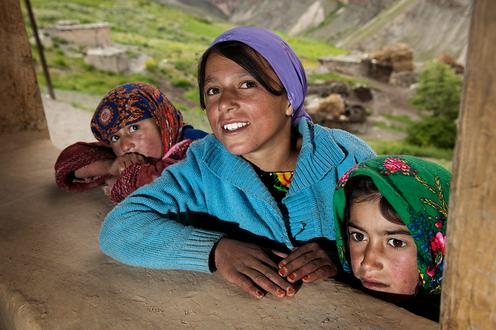

Yaghnobi children and women

But it is far from all Yaghnobis today who speak the language of their ancestors – many of those who were resettled have already forgotten the Yaghnobi tongue, with more and more of them using Tajik in their daily lives and communications.

Research fellow at the Institute of Language and Literature of the Tajik Academy of Sciences, Saifiddin Mirzozoda is himself originally from Yaghnob and has for many years been engaged in efforts to preserve the Yaghnobi language and culture. The linguist’s prognosis is not particularly optimistic: due to migrants’ assimilation, the Yaghnobi language is gradually being squeezed out of everyday use in favour of the language of state, and it is entirely possible that a few decades from now there will be no one left to speak it.

“In the villages where there is a high concentration of Yaghnobis, they speak in their native tongue. But among the families who live dispersed amongst the local population, for instance those living in apartment blocks, it is basically only the older generation who speak in Yaghnobi. The youth of course study at school and speak more often in Tajik,” Mirzozoda says.

Today the 17 Yaghnobi Valley villages are served by three elementary schools, where children are taught up until the fourth grade. Teaching at these schools is carried out in two languages – Yaghnobi and Tajik. Until 2005, schools in other parts of the country with a large Yaghnobi community also taught the native language, but following yet another education reform the number of hours devoted to it were decreased. “We want to reinstate these hours of class so that young people do not forget their native language. The new education minister (at that time Nuriddin Saidzoda – Fergana) supports us in this,” Mirzozoda said hopefully.

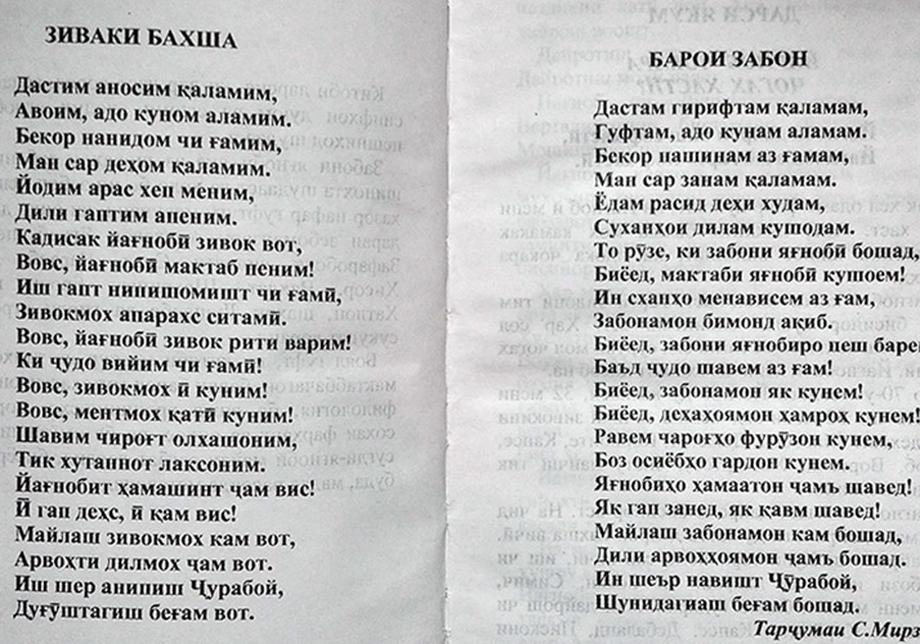

An elementary school in Yaghnob; Yaghnobi language schoolbooks for small children; a translation of a poem from Yaghnobi to Tajik

In 2009, a new law “On the language of state” was adopted in Tajikistan. Article 4 paragraph 2 of the law states that “The Republic of Tajikistan creates the conditions for the free use, protection and development of the Badakhshan (Pamiri) languages and the Yaghnobi language”. The necessary law, then, already exists. What is needed now are the corresponding measures and actions on the part of the relevant organs of state.

Meanwhile, local NGO Anahita is working hard to safeguard the Yaghnobis’ distinct cultural identity. With the help of funding from the American Christensen Fund, since 2010 Anahita has been carrying out a project to preserve the unique Yaghnobi cultural heritage for posterity. The organisation’s members work to gather as much as possible of the oral folklore of the Yaghnobis, handed down from generation to generation, together with their local customs and traditions, recording the accumulated photo, audio and video material in digital format.

A footbridge across the Yaghnob River; a local boy playing a dutar; a Yaghnobi wedding

“We see our job as helping to preserve Tajikistan’s biocultural diversity, in particular that of the Yaghnobi region, and drawing the attention of the national and international community to the issue. We have organised exhibitions and round tables devoted to the Yaghnobi language and culture. But the most important thing is that we want to create a digital record of the entire oral tradition of the Yaghnobis: their songs, their proverbs and sayings, their parables, legends and poetry. We want to document their customs and rites, which differ significantly from the rites of Tajiks in other regions. That way we can pass this heritage on to future generations. As part of the project we have already published the book Local Customs and Songs of the Yaghnobis, which describes their cultural distinctiveness. This is important above all for those Yaghnobis who currently live outside of their original homeland,” says Anahita director Vohid Safarov.

Among Safarov’s plans at present are the creation of an ethnopark in the Yaghnob River valley in order to preserve the irreplaceable nature and culture of this remarkable corner of the world.

Note from the editorial team: In May 2019, the Tajik government decided to establish a national park in the Yaghnob River valley. This remains the only conservation area in Central Asia which aims to protect not only the area’s landscape, flora and fauna, but also the customs, traditions and language of the local population. Vohid Safarov says that the next goal is to have Yaghnob included in UNESCO’s World Network of Biosphere Reserves.

Photos by Vohid Safarov and Nicolas Villaume

Fergana, 2015

-

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years

23 December23.12PhotoTokyo DriveJapan to invest about $20 billion in projects across Central Asia over five years -

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls

17 December17.12Sake for SixCentral Asia’s Rapprochement with Japan Comes with Hidden Pitfalls -

17 September17.09Risky PartnershipWhy Dealing with China Is Harder Than It Seems at First Glance

17 September17.09Risky PartnershipWhy Dealing with China Is Harder Than It Seems at First Glance -

06 August06.08What went wrong in Central Asia’s coronavirus response?How poor planning and a fixation on faulty test results undid months of hard work

06 August06.08What went wrong in Central Asia’s coronavirus response?How poor planning and a fixation on faulty test results undid months of hard work -

19 May19.05“I felt like a criminal”How Central Asia fought the coronavirus with quarantines – and appears to be winning

19 May19.05“I felt like a criminal”How Central Asia fought the coronavirus with quarantines – and appears to be winning -

17 April17.04A bad feelingAs one of the few remaining countries in the world yet to record cases, residents of Tajikistan are anxiously awaiting the arrival of COVID-19. Meanwhile, some doctors argue that the country experienced its first wave of the virus already last year...

17 April17.04A bad feelingAs one of the few remaining countries in the world yet to record cases, residents of Tajikistan are anxiously awaiting the arrival of COVID-19. Meanwhile, some doctors argue that the country experienced its first wave of the virus already last year...